Why I Turned Back the Clock with Movement—And You Can Too

Aging doesn’t have to mean slowing down. I used to feel stiff, tired, and resigned to “just getting older”—until I discovered how movement reshapes not just the body, but how we age. It’s not about extreme workouts or chasing youth. It’s about consistent, smart motion that supports longevity. This is what changed everything for me—and why science now backs it. The idea that our bodies must decline with age is deeply embedded in modern culture, but research increasingly shows that how we move—or don’t move—plays a far greater role than time itself. The good news? It’s never too late to start.

The Myth of Aging: Why We’ve Got It Wrong

For decades, society has accepted physical decline as an inevitable part of growing older. Many believe that stiffness, fatigue, and loss of strength are simply the price of aging. This narrative suggests that slowing down is natural, even necessary. But this belief is not only outdated—it’s inaccurate. While chronological age continues forward, biological aging is highly influenced by lifestyle choices, and physical deterioration is not a guaranteed outcome. In fact, studies show that up to 70% of how we age is determined by behavior, not genetics. This means that daily habits, especially physical activity, have a profound impact on how we feel and function as we grow older.

The problem begins with perception. When people accept fatigue or joint pain as “normal,” they often stop challenging their bodies. They avoid stairs, reduce walking, and limit daily movement, reinforcing a cycle of inactivity. Over time, this leads to muscle loss, reduced balance, and lower energy—conditions mistakenly attributed solely to age. But these changes are more often the result of disuse than time. The human body is designed to move, and when it doesn’t, systems begin to weaken. The idea that older adults should “take it easy” can actually accelerate decline rather than prevent it.

Additionally, cultural messages often portray aging through a lens of limitation. Media, advertising, and even healthcare settings sometimes reinforce the idea that older individuals are fragile or less capable. This can lead to self-imposed restrictions, where people avoid physical challenges out of fear or assumption. But the truth is, the body responds to demand. When movement is reintroduced—even gently—muscles strengthen, joints become more flexible, and energy levels rise. By reframing aging as a phase of potential rather than decline, individuals can reclaim agency over their health and well-being.

Movement as Medicine: The Science Behind Exercise and Aging

Scientific research now confirms that physical activity is one of the most powerful tools for healthy aging. At the cellular level, movement influences key biological processes that determine how quickly we age. One of the most studied markers is telomeres—protective caps at the ends of chromosomes that shorten with age. Shorter telomeres are linked to cellular aging and increased risk of chronic disease. However, studies have found that people who engage in regular physical activity tend to have longer telomeres, suggesting a slower biological aging process. This means that consistent movement may literally help cells stay younger longer.

Another critical factor is mitochondrial function. Mitochondria are the energy powerhouses of cells, and their efficiency declines with age, contributing to fatigue and metabolic slowdown. Exercise, particularly aerobic and resistance training, has been shown to improve mitochondrial health by stimulating the creation of new mitochondria and enhancing their performance. This boost in cellular energy translates to increased stamina, better recovery, and improved metabolic function—key components of sustained vitality.

Inflammation is another hallmark of aging, often referred to as “inflammaging.” Chronic low-grade inflammation is linked to heart disease, diabetes, and cognitive decline. Physical activity acts as a natural anti-inflammatory. Regular movement helps regulate the immune system, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory markers in the body. This protective effect is observed across all types of exercise, from walking to strength training, making movement a foundational strategy for long-term health.

The distinction between chronological age and biological age is crucial. Chronological age is simply the number of years lived, while biological age reflects the functional state of the body’s systems. Two people of the same age can have vastly different biological ages based on lifestyle. Exercise is one of the few proven ways to lower biological age. Longitudinal studies, such as the UK Biobank research, have demonstrated that individuals who maintain physical activity over time show slower rates of biological aging, better organ function, and reduced risk of age-related diseases. Movement, in this sense, is not just beneficial—it’s transformative.

My Turning Point: From Stiffness to Strength

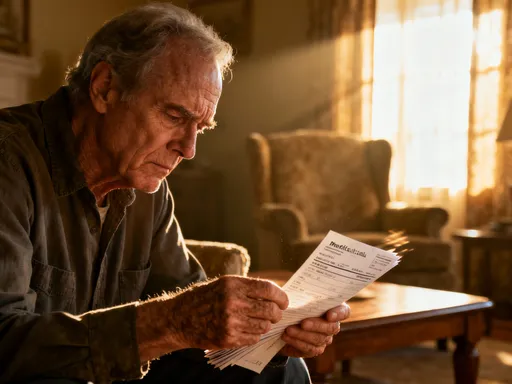

At 45, I felt older than I expected. Mornings began with stiffness in my knees and lower back. Simple tasks like carrying groceries or playing with my children left me exhausted. I attributed it to aging, assuming this was just how life would be from now on. I accepted that energy would wane and movement would become harder. But deep down, I missed the ease and strength I once took for granted. It wasn’t until a routine doctor’s visit, where my blood pressure and cholesterol were creeping upward, that I realized I couldn’t ignore my body any longer. The doctor didn’t prescribe medication—instead, she asked, “How much do you move in a typical day?” That question changed everything.

I started small. I committed to walking 15 minutes a day, just around the neighborhood. At first, it felt like effort with little reward. But within two weeks, I noticed subtle shifts—less stiffness, deeper sleep, and a slight lift in mood. Encouraged, I added gentle stretching in the mornings and a few bodyweight exercises like wall push-ups and seated leg lifts. I focused on form, not speed or intensity. I listened to my body, resting when needed, and celebrating small victories, like being able to bend down to tie my shoes without pain.

The emotional transformation was just as powerful as the physical one. As my energy returned, so did my confidence. I stopped dreading the stairs. I volunteered to help set up for school events. I even joined a community walking group, where I met others on similar journeys. Movement became less of a chore and more of a gift—a daily act of care that I gave myself. Over time, what began as a reluctant effort turned into a non-negotiable part of my routine. I wasn’t trying to look younger; I was learning to live better, stronger, and more fully in the body I already had.

The Types of Movement That Actually Work

Not all movement is created equal when it comes to aging well. The most effective approach includes a combination of resistance training, aerobic exercise, flexibility work, and balance training. Each type plays a unique role in maintaining health and independence. Resistance training, for example, is essential for preserving muscle mass. After age 30, adults lose 3–5% of muscle mass per decade, a condition known as sarcopenia. This loss slows metabolism, reduces strength, and increases fall risk. Lifting weights—even light ones—or using resistance bands two to three times a week can significantly slow this decline. It also supports bone density, reducing the risk of fractures.

Aerobic exercise strengthens the heart and lungs while improving circulation and brain health. Activities like brisk walking, swimming, cycling, or dancing increase oxygen delivery, enhance endurance, and support cognitive function. Research shows that regular aerobic activity can reduce the risk of dementia by up to 30%. For lasting benefits, experts recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week. The key is consistency and enjoyment—choosing activities that feel sustainable and pleasurable increases the likelihood of long-term adherence.

Flexibility and balance are often overlooked but are critical for maintaining independence. Stretching improves joint range of motion, reduces stiffness, and supports posture. Balance exercises, such as standing on one foot or heel-to-toe walking, help prevent falls—one of the leading causes of injury in older adults. Incorporating just 10 minutes of daily stretching and balance work can make a significant difference in mobility and safety.

Variety is essential. Relying on just one type of exercise limits overall benefits. A well-rounded routine combines strength, endurance, flexibility, and stability to create full-body resilience. This integrated approach not only supports physical health but also enhances confidence in daily activities, from carrying laundry to navigating uneven sidewalks. The goal is not performance but function—maintaining the ability to live actively and independently at every stage of life.

How Little Changes Create Big Results

One of the most empowering truths about movement is that small, consistent actions yield significant long-term results. You don’t need hours at the gym or intense workouts to make a difference. In fact, research consistently shows that regular, moderate activity is more effective for healthy aging than sporadic, high-intensity efforts. Just 20 to 30 minutes of movement most days of the week can improve cardiovascular health, boost mood, and enhance physical function. The power lies in repetition—showing up daily, even when motivation is low.

Integrating movement into daily life makes it sustainable. Simple changes, like parking farther from store entrances, taking the stairs, or doing calf raises while brushing your teeth, add up. Walking meetings, gardening, or dancing while cooking are practical ways to stay active without disrupting routine. Home workouts using minimal equipment—like resistance bands or bodyweight exercises—can be done in small spaces and fit into busy schedules. The idea is to remove barriers and make movement a natural part of the day, not an extra task to check off.

Tracking progress doesn’t have to mean weighing yourself or measuring inches. For aging well, better indicators include increased energy, improved sleep, greater ease in daily tasks, and enhanced mood. Keeping a simple journal to note how you feel—less stiffness, more stamina, better balance—can be motivating. These subtle shifts are often the first signs of improved biological health, even before visible changes appear. Celebrating non-scale victories reinforces the intrinsic rewards of movement and helps sustain long-term commitment.

Breaking Barriers: Common Excuses and How to Overcome Them

Despite knowing the benefits, many people struggle to start or maintain a movement routine. Common excuses include lack of time, low confidence, or fear of injury. But these barriers can be addressed with practical strategies. The belief that “I don’t have time” often stems from viewing exercise as a separate, time-consuming task. Reframing it as essential self-care—like brushing your teeth or eating meals—helps prioritize it. Even 10 minutes twice a day adds up. Scheduling movement like any other appointment increases accountability and reduces the chance of skipping it.

For those who feel they’re “not athletic,” the solution is to find enjoyable activities. Exercise doesn’t have to mean running or weightlifting. It can be tai chi, water aerobics, dancing, or walking with a friend. The best form of movement is the one you’ll actually do. Trying different options and paying attention to how each makes you feel can help identify what works best. Accessibility matters—choosing activities that fit your current ability level ensures safety and builds confidence over time.

Fear of injury is a valid concern, especially for those with joint pain or prior health issues. The key is to start slowly, focus on proper form, and listen to your body. Consulting a physical therapist or certified trainer can provide personalized guidance. Low-impact options like swimming or cycling reduce joint stress while still delivering benefits. Pain should never be ignored—discomfort is normal when starting something new, but sharp or persistent pain is a signal to stop and reassess. Movement should empower, not harm.

Building a Lifetime Habit: Making Movement Sustainable

Sustaining movement over a lifetime requires more than motivation—it requires a shift in mindset. Instead of viewing exercise as a punishment for eating too much or a way to look a certain way, it’s more effective to see it as an act of self-respect. Every time you move, you’re investing in your future self—your strength, independence, and quality of life. This perspective fosters intrinsic motivation, which is more powerful and lasting than external goals.

Designing a routine that evolves with age and ability is essential. What works at 40 may need adjustment at 60. The ability to adapt—switching from running to walking, from heavy weights to resistance bands—ensures continuity. Regular self-assessment helps identify what the body needs at different stages. Some days call for energy-building activity; others require gentle stretching or rest. Flexibility in routine prevents burnout and supports long-term adherence.

Community and accountability also play a vital role. Exercising with a friend, joining a group class, or sharing progress with family increases commitment. Small wins—like walking an extra block or holding a balance pose longer—should be acknowledged and celebrated. These moments build momentum and reinforce positive behavior. Over time, movement becomes less of a habit and more of a way of life—a natural expression of caring for oneself.

Aging well isn’t about stopping time—it’s about moving with it. The body thrives on use, and every step, stretch, or lift is an investment in vitality. This isn’t a quick fix, but a lifelong practice. Start where you are. Move often. Age boldly.