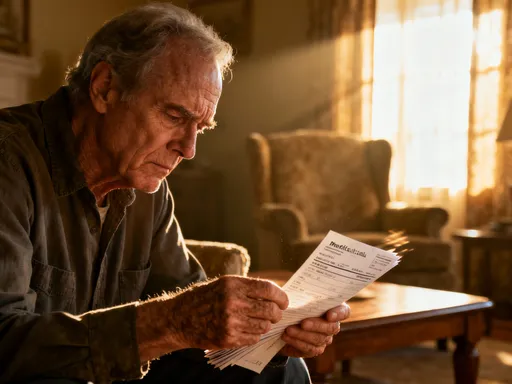

What If Your Health Costs Skyrocket After 60?

Imagine retiring peacefully, only to face a medical bill that wipes out your savings. I’ve seen it happen—friends, family, even myself once underestimated the financial weight of aging. Healthcare isn’t just about insurance; it’s about protecting your life’s work. That’s why smart wealth management for medical reserves isn’t optional. It’s the backbone of a secure retirement. Let’s explore how to build that protection without stress or guesswork. The reality is this: by age 65, the average American has a 70% chance of needing some form of long-term care. Yet fewer than 30% have planned for it financially. Medical costs after 60 aren’t outliers—they’re expected. And without preparation, they can dismantle decades of careful saving. This isn’t fear-mongering; it’s financial realism. The goal isn’t to eliminate uncertainty, but to create a buffer strong enough to absorb it.

The Hidden Cost of Long-Term Health

Most people think of healthcare as doctor visits, prescriptions, and the occasional test. But in later life, medical expenses evolve into something far more complex and costly. Chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, or arthritis don’t just appear—they grow over time, often requiring ongoing treatment, monitoring, and lifestyle adjustments. These are not one-time costs; they are recurring financial obligations that can last 10, 20, or even 30 years. A single diagnosis can add thousands of dollars annually to a household budget, and many retirees face multiple conditions simultaneously. What’s more, standard health insurance rarely covers everything. Medicare, for instance, pays about 80% of approved services, leaving beneficiaries responsible for the rest—what’s known as cost-sharing. Without planning, these out-of-pocket expenses accumulate silently, eroding savings over time.

Long-term care is another major blind spot. Many assume nursing homes or in-home care will be covered by insurance or government programs. But Medicare does not cover custodial care—such as help with bathing, dressing, or eating—unless it’s part of skilled nursing following a hospital stay. Medicaid does cover long-term care, but only after individuals have spent down most of their assets to meet eligibility requirements. This means families often face a painful choice: deplete their wealth to qualify for assistance or pay privately, where annual costs can exceed $100,000 depending on location and type of care. A 2023 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that 52% of Americans turning 65 today will need long-term care services at some point, with nearly 25% requiring care for five years or more. These aren’t rare events; they are statistical norms.

Then there are the hidden costs—transportation to appointments, home modifications for mobility, assistive devices, and even dietary changes for medical conditions. These may seem minor individually, but they add up. A walker, a stairlift, or a modified kitchen can cost thousands. Prescription drugs, especially specialty medications for cancer, autoimmune diseases, or neurological disorders, can run into hundreds or even thousands per month. And as life expectancy increases, so does the duration of exposure to these expenses. The truth is, medical costs in retirement are not just high—they are unpredictable in timing, severity, and duration. That’s why treating them like any other budget line item is a dangerous oversimplification. They require their own dedicated planning framework, one built on foresight, flexibility, and resilience.

Why Traditional Savings Aren’t Enough

Many retirees rely on traditional savings accounts, pensions, or 401(k) plans to cover unexpected medical costs. While these are essential components of retirement planning, they are often insufficient when faced with sustained health challenges. The problem lies in the mismatch between the nature of savings and the reality of medical spending. Traditional savings are typically static—funds are deposited and grow slowly, if at all, in low-interest accounts. But medical costs rise much faster than general inflation. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, healthcare inflation has consistently outpaced overall inflation by 1.5 to 2 times over the past two decades. This means that a dollar saved today will buy less medical care in the future, even if the account balance appears stable.

Consider this: a retiree with $50,000 in a standard savings account earning 0.5% interest will see that balance grow to about $55,000 over 10 years. But if medical costs rise at 5% annually—well within historical trends—the same services that cost $10,000 today would cost nearly $16,300 in a decade. The purchasing power of savings diminishes rapidly, leaving retirees exposed. Pensions and fixed-income streams face similar challenges. They provide predictable income, but rarely adjust for healthcare-specific inflation. Social Security benefits do include a cost-of-living adjustment, but it’s based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), which doesn’t fully reflect the spending patterns of older adults, particularly their higher proportion of healthcare expenses.

Another issue is liquidity and access. Retirement accounts like IRAs and 401(k)s are designed for long-term growth, but they come with restrictions. Withdrawals before age 59½ typically incur penalties, and required minimum distributions (RMDs) begin at age 73, regardless of whether the money is needed. More importantly, tapping into these funds during a health crisis—especially if it coincides with a market downturn—can lock in losses. Selling investments at a low point to pay for surgery or medication means realizing a loss while also depleting future income potential. This double penalty is a common but avoidable trap. Additionally, relying on home equity through reverse mortgages or sales introduces its own risks, including loss of housing stability or reduced inheritance for heirs.

The bottom line is that traditional savings serve important purposes, but they are not optimized for the unique demands of medical expenses. They lack the targeted growth, accessibility, and protection features needed to handle high-cost, unpredictable health events. That doesn’t mean abandoning them—it means complementing them with a more strategic approach. A dedicated medical reserve, structured differently from general savings, can bridge the gap between what traditional accounts offer and what healthcare realities demand.

Building Your Medical Reserve: The Core Principles

A medical reserve is not a single account or product—it’s a strategy built on three core principles: liquidity, stability, and growth alignment. Liquidity ensures that funds are available when needed, without penalties or delays. Stability protects the principal from market volatility, especially during times of health crisis when emotional and financial stress are high. Growth alignment means the reserve grows at a rate that keeps pace with, or slightly exceeds, healthcare inflation, preserving purchasing power over time. Together, these principles form a foundation that supports both immediate needs and long-term preparedness.

Liquidity is critical because medical expenses often arise suddenly. A fall, a diagnosis, or an emergency procedure can create urgent financial demands. Accessing funds should be simple and penalty-free. High-yield savings accounts, money market funds, and short-term certificates of deposit (CDs) are suitable vehicles for this portion of the reserve. They offer modest returns with minimal risk and immediate access. The key is to keep this layer separate from other savings so it remains untouched for non-medical use. Experts often recommend setting aside 6 to 12 months of anticipated medical expenses in this liquid tier, adjusted for individual health history and family risk factors.

Stability comes from minimizing exposure to market swings. While stocks offer higher long-term returns, they are too volatile for funds needed in the near term. A retiree facing surgery shouldn’t have to worry about whether a market crash has reduced their ability to pay the hospital bill. Fixed-income assets like bonds, bond funds, or stable value funds provide more predictable returns and lower volatility. These are appropriate for the mid-term portion of the medical reserve—funds expected to be used in 3 to 7 years. Diversification across different types of fixed-income securities can further reduce risk without sacrificing all growth potential.

Growth alignment requires a careful balance. Since medical costs rise faster than general inflation, the reserve must grow at a comparable rate to maintain its value. This doesn’t mean aggressive investing, but rather thoughtful exposure to assets with moderate growth potential. For those in their 50s or early 60s, a small allocation to dividend-paying stocks or balanced mutual funds may be appropriate. As one approaches 70 and beyond, the emphasis should shift toward preservation. The goal isn’t to maximize returns, but to outpace healthcare inflation by a reasonable margin—say, 4% to 6% annually—without taking on excessive risk. Regular reviews and adjustments ensure the reserve stays aligned with changing needs and market conditions.

Strategic Asset Allocation for Health Security

Effective medical reserve planning uses a tiered asset allocation model, much like a well-structured retirement portfolio. This approach divides the reserve into layers based on time horizon and risk tolerance. The first tier—immediate needs—holds highly liquid assets for expenses expected within the next 1 to 2 years. This could include doctor visits, medications, or minor procedures. The second tier—mid-term needs—covers anticipated costs in 3 to 7 years, such as planned surgeries, increased medication use, or early-stage long-term care. The third tier—long-term protection—addresses future uncertainties, including extended care, chronic disease management, or end-of-life services. Each tier uses different investment vehicles tailored to its purpose.

The immediate tier should prioritize safety and access. High-yield savings accounts, insured money market funds, or short-term CDs are ideal. These accounts are protected by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) up to $250,000 per institution, offering peace of mind. The mid-term tier can include intermediate-term bonds, bond ladders, or conservative balanced funds. A bond ladder, for example, involves purchasing bonds with staggered maturity dates, providing a steady stream of income and reducing interest rate risk. This layer may also include fixed annuities, which offer guaranteed returns over a set period and can be structured to avoid early withdrawal penalties.

The long-term tier is where strategic tools like health-linked insurance riders or deferred annuities with long-term care benefits come into play. Some life insurance policies offer chronic illness or long-term care riders that allow policyholders to access a portion of the death benefit while alive if they need care. These can be powerful tools, especially when premiums are locked in at younger ages. Deferred annuities with care benefits provide a future income stream that can be used for medical expenses, with built-in protection against market loss. While these products require careful evaluation and are not suitable for everyone, they can add a layer of security for those concerned about catastrophic costs.

Allocation percentages should reflect individual circumstances. A healthy 60-year-old might allocate 30% to liquid assets, 50% to fixed income, and 20% to growth-oriented assets. By age 75, that mix might shift to 50% liquid, 40% fixed income, and 10% growth, reflecting reduced life expectancy and increased need for immediate access. Regular rebalancing ensures the portfolio stays aligned with changing health status and financial goals. The key is to avoid a one-size-fits-all approach and instead tailor the structure to personal risk factors, family history, and retirement timeline.

Risk Control: Avoiding Common Financial Traps

Even the best-laid plans can fail if they don’t account for behavioral and systemic risks. One of the most common mistakes is overestimating insurance coverage. Many retirees assume Medicare, supplemental plans, or retiree health benefits will cover most medical costs. While these programs provide essential protection, they leave significant gaps. Medigap policies help, but they don’t cover everything—long-term care, dental, vision, and hearing are often excluded or only partially covered. Relying solely on insurance without a financial buffer is like driving a car with seatbelts but no airbags—it offers some protection, but not enough for a major impact.

Another trap is procrastination. People often delay medical reserve planning until a health issue arises. But by then, options are limited. Insurance premiums rise with age and health status. Investment time horizons shrink. The ability to build savings diminishes. Starting early—even in one’s 50s—allows time for compounding growth and more favorable insurance rates. A 55-year-old in good health can secure a long-term care insurance policy at a fraction of the cost a 70-year-old would pay, if they qualify at all.

Emotional decision-making during a crisis is another major risk. When facing a serious diagnosis, families may make rushed financial choices—cashing out retirement accounts, taking on high-interest debt, or selling a home prematurely. These decisions can have long-term consequences. For example, withdrawing $50,000 from a 401(k) during a market downturn not only depletes savings but also reduces future growth potential. If the market recovers, the lost gains may never be recaptured. Having a pre-established medical reserve reduces the pressure to make such decisions under stress.

Finally, some rely too heavily on family support, assuming children will help cover costs. While family assistance can be valuable, it’s not a reliable financial plan. Adult children may have their own financial obligations—mortgages, education costs, retirement savings. Expecting them to bear the burden can create tension and strain relationships. A sound medical reserve respects both personal independence and family harmony by ensuring that care costs don’t become a shared financial crisis.

Practical Tools and Habits That Work

Planning is only effective when it’s actionable. The most successful retirees don’t rely on complex strategies—they adopt simple, consistent habits. One of the most powerful is the annual medical cost review. Every year, set aside time to assess current and projected medical expenses. Track prescriptions, doctor visits, lab tests, and any new diagnoses. Compare this to the previous year and look for trends. Is medication use increasing? Are specialist visits becoming more frequent? This data helps refine reserve estimates and adjust savings goals.

Another habit is dynamic budgeting. Instead of treating the medical reserve as a fixed amount, treat it as a living part of the financial plan. As health changes, so should the allocation. A new diagnosis may warrant increasing the reserve; improved health might allow for a slight reallocation. Linking reserve reviews to health milestones—like annual physicals or medication renewals—creates natural check-in points. Digital tools can support this process. Personal finance apps, spreadsheets, or even simple journals can track medical spending over time, making patterns visible and adjustments easier.

Working with a financial advisor who understands healthcare planning can also make a difference. A qualified professional can help evaluate insurance options, model different health scenarios, and recommend appropriate investment vehicles. They can also provide objective guidance during emotionally charged moments, helping families avoid impulsive decisions. The goal isn’t to outsource responsibility, but to gain clarity and confidence.

Finally, consistency matters more than perfection. Setting aside even $100 a month in a dedicated medical savings account can grow into a meaningful buffer over a decade. Automating transfers ensures the habit sticks. The power lies in repetition—small, regular actions that compound over time, much like health habits themselves. Just as daily walks build long-term fitness, consistent financial habits build long-term security.

A Lifetime Approach to Financial Wellness

Medical reserve planning isn’t a one-time task; it’s a lifelong practice of stewardship and foresight. It reflects a deeper commitment to personal dignity, independence, and peace of mind. No one can control their health destiny, but everyone can influence their financial readiness. The goal isn’t to eliminate risk—that’s impossible—but to build a structure that absorbs shocks without collapsing. This means viewing healthcare not as an expense, but as an investment in quality of life.

The most secure retirees are not those with the largest portfolios, but those with the most thoughtful plans. They understand that wealth isn’t just about accumulation; it’s about preservation and purposeful use. A well-structured medical reserve doesn’t guarantee perfect health, but it does guarantee options. It means choosing care based on medical need, not financial fear. It means maintaining control over living arrangements, treatment choices, and family dynamics.

Starting early, staying informed, and adjusting regularly are the pillars of this approach. It’s never too late to begin, but the earlier the start, the greater the advantage. Whether you’re 50, 60, or already in retirement, the principles remain the same: protect liquidity, manage risk, and align growth with real-world needs. With discipline and care, it’s possible to face the later years with confidence, knowing that no matter what health challenges arise, the financial foundation is strong enough to support them. That’s not just smart planning—that’s true peace of mind.